Uncertain Times Call for Regenerative Design

Sesh, Senior Strategist in frog London, shares why the climate crisis and COVID-19 pandemic have encouraged her to explore regenerative design methods. And why everyone should grit their teeth and read the depressing climate change articles.

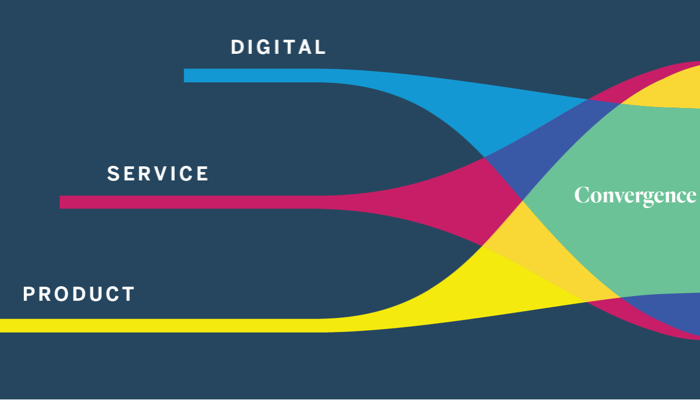

On this episode of the Design Mind frogcast, we speak with Sesh Vedachalam, a strategist in the frog London studio. Sesh brought the topic of regenerative design to our attention after months of self-directed research through a program called a ‘Learning Marathon.’ With roots in agriculture, architecture, material design and ecological design, regenerative design is an evolution of the design practice that helps us imagine not just better individual products and services, but more dynamic, more sustainable and more adaptive systems for our designs to live within.

See a recommended reading list from Sesh below, listen to the podcast episode and read the transcripts to learn why times of crisis require regenerative design techniques, why systems thinking is more important than ever, and why the pandemic could actually be the biggest design challenge of our lives.

Recommended Reads in Regenerative Design

By Sesh Vedachalam

I’ve spent the last year or so, exploring this question.

It is a question that is intentionally broad and open because I don’t know what I don’t know. I did know that mainstream climate reporting wasn’t giving me the depth of understanding I was looking for and neither was it helping me understand how we could act beyond the micro, individual actions.

If you’re anything like me, you have probably read news, articles and books about the climate crisis with a sense of dread and doom. Maybe you felt like you wanted to do something. Maybe you protested, made lifestyle changes and shopped more ethically. But at the same time you may have still found yourself thinking, ‘This problem is so big—and so urgent. With so much resistance and inaction, how can anything we do possibly make a difference?’

I used to think this feeling of overwhelm and dread was because I hadn’t been paying as much attention to the problem or the solution. If I just learned more, I’d know what to do. BUT. That’s not how it works.

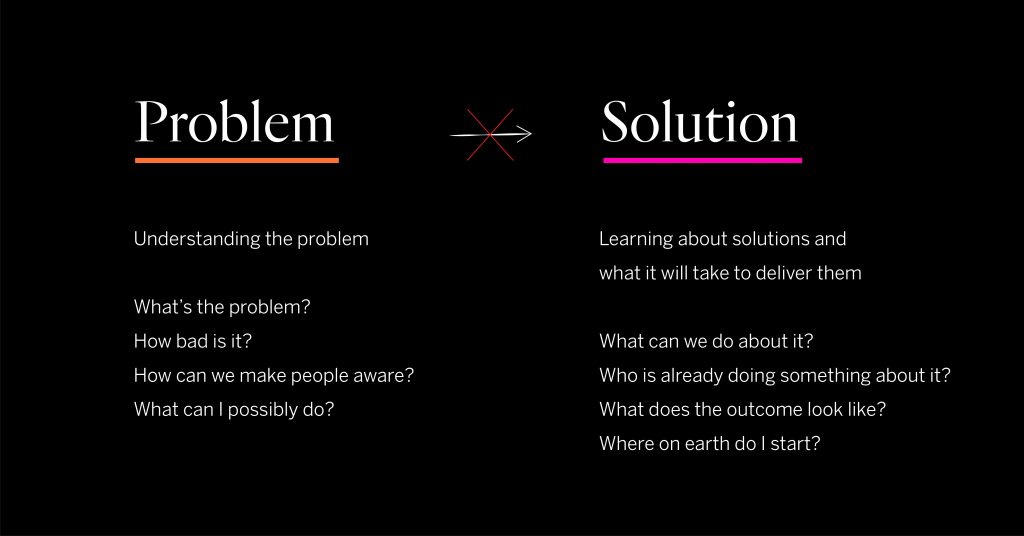

Understanding the problem and potential solutions in some depth is necessary, but not enough. A linear problem solving approach won’t work here.

<

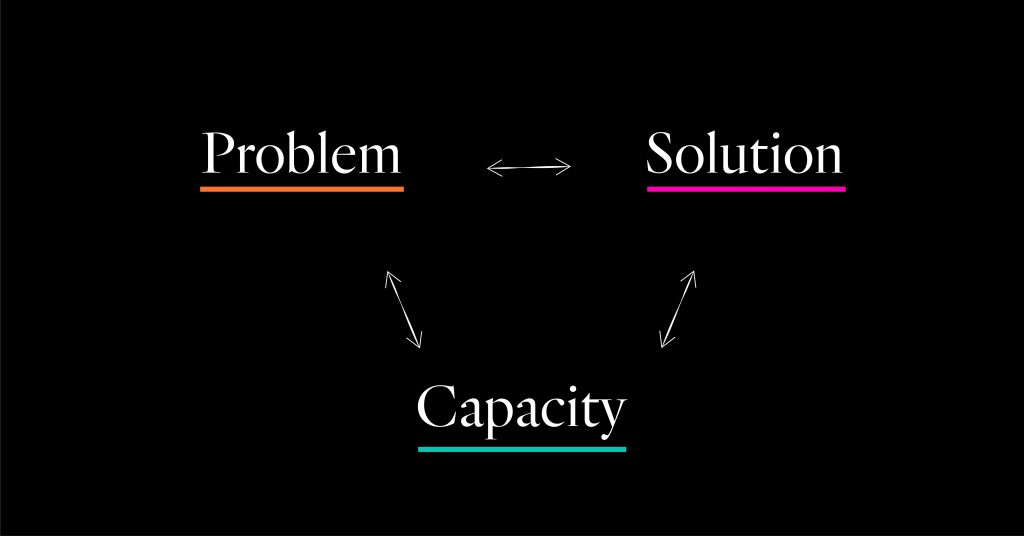

Beyond understanding the problem and learning about the solutions, we need to hold space for our very human reactions to this very existential crisis. This has been one of my biggest ‘aha moments’ during this exploration. I’ve learned it is entirely normal and expected for us to feel a wide spectrum of things, and for us to have varying capacities—mental and emotional bandwidth—to take things on.

The capacity space is really rich and interesting. It helps us with more complex questions like, ‘How can we face this existential and scary thing and still have the hope and strength to act?’

<

I have been using the framework of the problem, solution and capacity spaces to organize my thinking around how the practice of design and innovation needs to evolve to meet the existential challenge and enormous opportunity.

But for today, I’ll use this as a framework to provide some reading recommendations. I’m recommending books, but you could just as easily begin with some excellent articles and videos featuring these authors. I recommend balancing your reading about the climate crisis along these three dimensions. Each dimension helps you explore a different question:

- How do we understand the scope scale and urgency of the problem, and also the nature of the problem? Why has it been hard for us to collectively understand and grapple with it?

- What solutions are out there? What kind of world will those solutions build?

- How can we build our individual and collective capacities for change and resilience?

The most common pattern I see is that many of us start reading about the problem, only to soon feel overwhelmed and terrified and then think all hope is lost. For example, we may we read the latest article about Arctic ice not refreezing in the Guardian and feel too powerless to act. This is a rational response to the latest scientific conclusions, but it’s not the most productive one. To paraphrase Hans Rosling in Factfulness, merely reading the news is like relying on junk food for all your nutrition. It’s highly unbalanced. By definition, the news tends to covers events that are sudden and dramatic. But we need to go beyond that to see the full picture.

Good for: Illuminating the problem space and defining the solution space

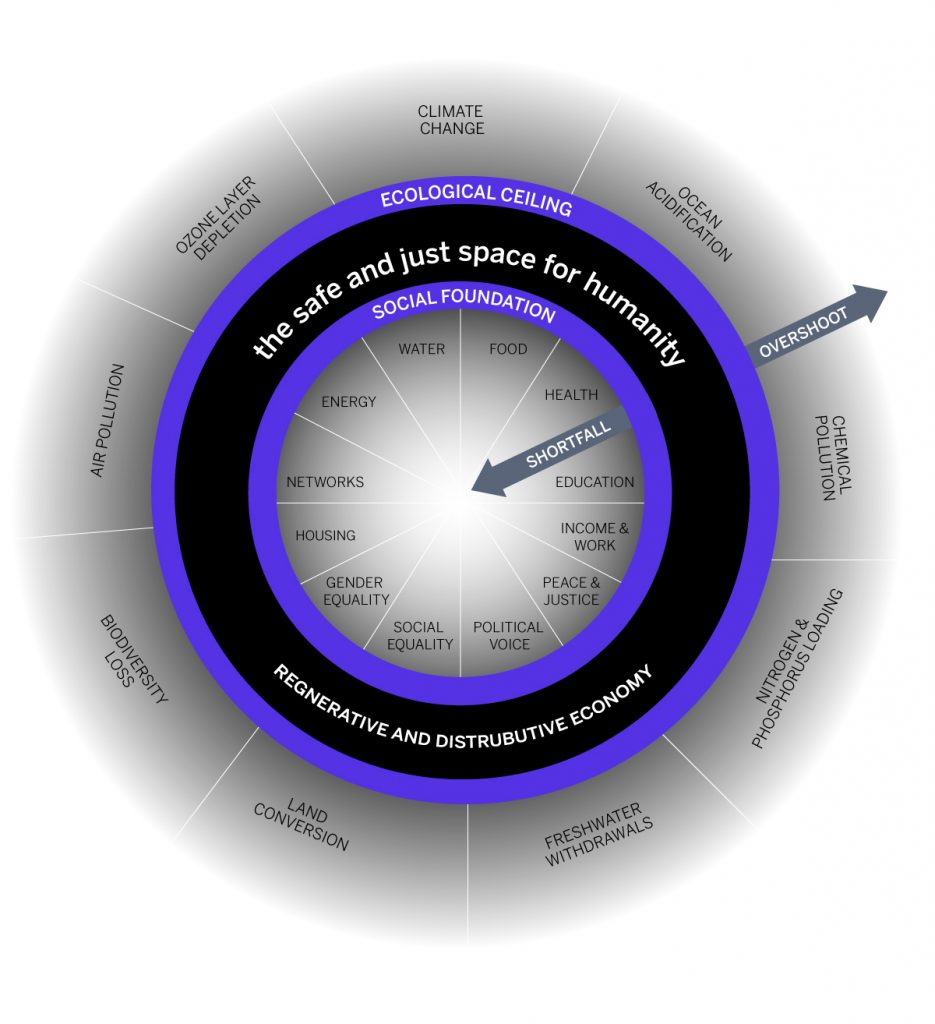

If you are looking to understand the crisis facing us using a macro, systems lens, I recommend Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth. Other than one Econ 101 class I took in business school, I’ve had no economics training so I was hesitant to dive into this book, thinking that I may not be the right audience for it. But as I flipped through the pages, the doughnut diagram caught my eye and I was instantly struck by how intuitive and powerful it seemed.

<

Raworth’s framework, with its simple yet powerful framing of an ecological ceiling and social foundation shows us how to frame a new kind of future, policy structure and economic system.

In design and in systems-thinking, the idea of constraints is really powerful. The right kind of constraint can guide our approach and unleash our creativity. The doughnut’s floor and ceiling can be powerful enabling constraints to imagine a new kind of future that works for all life on the planet.

Beyond the framework itself, the book is a fascinating read full of powerful examples and stories of how the systems and policies that shape our economic and financial systems came to be. We see how the seemingly immovable ‘truths’ shaping our world were born out very human biases.

Good for: Understanding the breadth of regenerative and equitable solutions. Solutions have also been ranked by level of impact

Yes—things are bad. But the climate crisis isn’t just a story about apathy, denial and inaction (by governments and individuals.)

There is an incredible amount of action. Being informed about the problem is good, but doing only that is likely to paralyze us into inaction. This is why I like books like Drawdown. It is less a narrative and more of an inspirational glimpse into a world that is possible and within reach.

They list multiple solutions, ranging from silvopasture agriculture techniques, to educating girls, to building green roofs and bike infrastructure in cities. The projected carbon emissions reduction, net implementation costs and net savings are also presented for each solution.

I particularly like how the authors talk about how to read the book. “The logical way to read this book is to identify how you can make a difference,” writes Paul Hawken.

They go on to clarify they aren’t talking about making a difference as an individual. Many of these things need to happen at a systemic level, but we can compound individual action into the power of movements.

“Movements are what take five or ten percent of people and make them decisive—because in a world where apathy rules, five or ten percent is an enormous number,” writes Bill McKibben in Drawdown. McKibben is also author of The End of Nature (1989).

Good for: Understanding how we can increase individual and collective capacities for change

Active Hope is firmly in that third dimension of Capacity-building. This is an area I didn’t know anything at all and has been one of my richest learnings from my exploration.

Paying attention to the capacity space is critical to bringing people into the fold, to give them hope that they can make a difference—that it isn’t too late—and to sustain them while they’re on the path to making change.

The authors of Active Hope talk about how our ability to respond is shaped by the stories that we have available to us. They lay out the three ongoing narratives of our time: the story of “Business as usual” (the world we’ve known so far and often think we have no choice in, where endless economic growth is viewed as essential), the “Great Unraveling” (this is the bad stuff—the ecological and social disasters that the first story is drawing us toward) and the “Great Turning” (this is the good stuff—new possibilities for a regenerative and equitable future).

The Great Turning is described in the book as being about “new and creative human responses […] the epochal transition from an industrial society committed to economic growth to a life-sustaining society committed to the healing and recovery of our world.”

The book isn’t academic or conceptual about hope and capacity. It is refreshing, practical and actionable about things that may seem fuzzy or hard to pin down. It offers exercises and prompts for you to start to build your practice of Active Hope.

Bonus:

If you’re further interested in the capacity space, story-led change making and interbeing, you might like to read Climate: A New Story by Charles Eisenstein.

I’m also widening my frame of the solution space to include ideas drawn from traditional practices and indigenous wisdom. Try Sand Talk by Tyson Yunkaporta for more on this.

Episode Transcript:

Design Mind frogcast

Uncertain Times Call for Regenerative Design

Episode 2

[01:18]

We have this convenient myth as just human beings in general that we are separate from nature. We’ve conquered nature somehow and we’ve put it into these little boxes and we live here and nature is out there. But that’s not quite true. And some of this thinking comes from outdated economic models that kind of treated nature in this particular way. They ignore the natural world as an unimportant variable. And for many of us living in cities, and myself included, we don’t have a lived connection to the natural world. So it’s very easy to kind of forget that. But we’re increasingly understanding just how interrelated and interdependent everything on this planet is. And even in this current crisis, we’re seeing just how interdependent so many systems are. So all of us are locked down for a few months and we see just our cities transform. Outside of my window, there’s so many more seagulls. I’ve never heard seagulls in London before.

[02:18]

My name is Sesh. I’m a strategist in the Frog London studio, and I help clients understand and unpack the challenges that they have, how it can be translated to real products, services and experiences, and also how do we make those things real, market ready and successful in the world.

[02:40]

Regenerative design is kind of a whole systems approach to design. So we’re talking about processes that sort of renew and revitalize the sources of energy and materials that we’re using. We’re considering products across their whole life cycle of being, so not just how it’s made, how it’s used, but also how it repairs, how you might repair it, how it might break down, how it might interact with communities, how it might interact with the local sort of biosphere as well. So it’s sort of design that considers the whole system in which our design sits.

[03:15]

We all live within systems. So we all are living within big systems and small. So an organization is a system, society is a system, a group of companies that form a particular industry is a system. How we interact with governments and health care and bigger sort of these units of our society, our systems as well.

[03:37]

It’s important to kind of understand climate change as a systemic problem. The sort of simpler solution might seem to be, OK, let’s find ways to control the weather or the climate then, right? I mean, no one in sort of modern climate science is talking about these things, of course. But you can tell even from a few years ago, if you watch some sort of climate disaster movies, there’s stuff like, ‘There was a there’s a satellite that controls the weather and like so that’s how we solved climate change!’ These things don’t work because the fundamental reasons that got us into this mess, those haven’t stopped. So if you don’t understand things from a systemic perspective, you might just be putting bandaids on things and exacerbating the problem because the underlying causes haven’t really been addressed. We need to be looking at, well, what in the system is the most powerful sort of lever for change? And can we be working there rather than working on the outskirts, or on the symptoms rather than the cause?

The Role of Design During Crisis

[04:46]

Design is the choices we make about the world we want to live in. Right? We can’t pretend we live in a bubble where some of the bigger issues of our times don’t actually matter. They do. And by not seeing that, we might not be doing the best design work that we want to be doing. So it feels like essential to be considering that.

[05:09]

I don’t think there’s a line between design and activism. So, nothing nothing we do is neutral, right? And this isn’t just true in design. It’s true in technology where we’re talking about how algorithms aren’t neutral. They carry the same biases of the people that write them. Similarly, the design choices we make aren’t neutral. Every choice we make is sitting inside of a system, and that system is functioning in a particular way. So our design choices are ultimately supporting and perpetuating certain systems, certain behaviors that we should be aware of. And to not be activist is kind of like saying we we want to take the lazy way out here. We don’t really want to do the work to understand how our designs are meeting the world. And that seems like a pity because we have the skills to help people imagine a new future.

[06:14]

From all of the research that I’ve been doing, the frameworks that I’ve learned, or different topics or different experts that I have now learned about that’s already informed of some of the work, the projects that we’ve been doing over the last few months, so we did a project with UNICEF and ARM recently to help them sort of map out their five year partnership strategy. And we used a futures practice called the Three Horizons Framework, which is something that I learned about during this exploration. And it’s a really, really powerful tool to help people map out what are their needs for not just innovation, but what is what is your whole portfolio of activity that you have currently and how can you use that framework to manage both the things that you need to be doing now? Your pressing business as usual needs, but how can you shape a portfolio of innovation that kind of pushes you to a radical regenerative new future?

[07:08]

So one of the key learnings for me in sort of exploring regenerative design as a practice is not just, you know, what new frameworks or tools or methodologies or processes we might be using in this new practice. But also how do we collaborate differently? How do we be as humans, as team members, as leaders of our organizations? Because it’s sort of very clear to me that we need to fundamentally shift our approaches to how we think about leading and collaborating if we are to make some of these changes in the world. And there’s a lot more to be said about that. What kind of mindsets and skills that we need to develop collectively to be doing this work. But that’s definitely a key part of defining the practice, is also defining how we learn together, how we do together better than we do now.

What we’re seeing with regenerative design is we have to rethink our idea of this perpetual growth. And you can’t do that kind of work in a system without that system kind of pushing back against you. So you have to kind of call on all of our skills of influence and persuasion and sort of multi-stakeholder management for us to be able to effectively bring about some of these changes. And it’s sort of pushing back against the idea of short term thinking in businesses. And this isn’t a new idea at all. Clayton Christensen talks about kind of how businesses are in this loop of thinking and marginal thinking, for example, or they’re just focused on quarterly results at the risk of not seeing the long term, the big picture. And we’ve always talked about this in the context of, oh, if you don’t think long term enough, somebody might disrupt you, a competitor might disrupt you. But it’s the same same thing. If we’re not taking a long enough view, then you’re not seeing some of the other macro challenges that are facing the your business or your industry or society at large.

Finding Comfort in Uncertainty

[10:14]

Maybe it’s comforting for a lot of people to cling on to the oh, I just want things to go back to normal. And that’s that’s fine. We all kind of want that back, but we can’t have all of it back and maybe some of it wasn’t that great anyway. So why not imagine something new?

[10:32]

Historically, if you go deep into history, I think even in the Roman times and also the medieval times, all of these big plagues were followed by sort of periods of massive political, social, economic upheaval. So right after the Black Death in Europe in the 13th, 14th centuries, we had the Renaissance period. They even say that the 1918 flu, which happened alongside the World War One, there were sort of changes that happened in society that were a direct impact of the of the pandemic at the time.

[11:23]

The only certainty is uncertainty. So talking about how how we can develop the muscles to help people exist in a state of uncertainty, not jump quickly to solutions, but really be OK with staying with questions rather than answers. Rebecca Solnit says despair, or feeling like everything is doomed, is a form of certainty. It’s saying that is what will happen. And in the same way, optimism that everything will be fine is also another kind of certainty. And if we’re certain about things, then we don’t do anything about it. So either we are sure things are not going to work out or we’re sure things are going to work out. And neither of that would lead to any real change.

The Power of Learning

[12:15]

I sometimes think that I do this job because I have the sort of FOMO about not knowing everything in the world. And yeah, I mean, every, every project we do is, you know, it’s completely new for us. It’s sort of needing to become fast experts on something very quickly and just gaining enough expertise that you’re able to ask smart questions to our clients who are sort of who have the depth of expertise in their fields. But we are bringing the perspective that is coming from looking at many different problems across many different industries. And we’ve understood their problems face enough to be able to probe and expand the problem in an interesting way. And for me, learning is the way that we I can do this job more effectively. So design is constantly evolving and not just design. I think everything is constantly evolving and we all kind of have to keep learning. But as designers, we can start by sort of visualizing some of the complexity so that we can help our clients see some of the cause and effect so that they are understanding clearly where the most powerful interventions can be. And a lot of the times as designers, we say, well, that, you know, our scope is limited and we don’t have right now within the budget within this time or within the client sort of power to do something. These problems are bigger than that. OK, great.

[13:35]

But the fact that we’ve put it out on the table, we’ve we’ve said these are the problems and these are where more effective interventions can be, means that you have at least revealed that and you’ve come to a shared understanding of the problem that is more accurate than what we all had collectively before, for example, in the early stage where we talk about reframing the problem. So that is a moment where we can reframe much more boldly than we have done before. So going beyond the scope of, you know, a much more beyond the scope of not just looking at that product, that organization, but also just looking at the context in which it sits in and the markets that it might live in and the and the sort of impact it might have on communities or something like that.

[14:20]

And then you when we’re exploring and when we’re creating, it’s doing that more deeply. So some of the principles there are like who do we choose to talk to in the use of research? Right. So being much more intentional about making sure we’re getting voices that aren’t just sort of the typical target audience for that product or something like that, but to thinking more intentionally about who it might impact and making sure some of those voices are coming in to such a regenerative design approach can lead to more resilient, inclusive organisations and business models that draw on more expansive, if unlikely, paths to innovation. There are there are actually practices where they’re talking about indigenous wisdom and how can we sort of bring that back? So thinking of innovation, not just as the new and shiny, but also looking backwards into how have people in a particular community and a location, how have they solve these problems? Perhaps in the past?

On Radical Hope

[15:22]

To have a sort of radical hope is to have the courage and the perseverance to really look at what we’re facing. And in the face of that, in the face of just the overwhelming thing in front of us, we can find ways to sort of creatively and intentionally hope. And hopefully and that leads us maybe we don’t know exactly what the what the sort of outcome of that might be. But we know we want it to be a sort of a better more just more of a generative world if you haven’t really taken the time or you’ve kind of been avoiding the really depressing climate change articles, just grit your teeth and read some of them because you kind of need to know the landscape that you’re standing in, the ground that you’re standing on to then make decisions about, OK, what do we then want to do and where do we want to go?

[16:16]

And I don’t say this to just make people feel sad about things. We’re probably going to have some serious consequences of this crisis and some of. It’s already here. There’s also incredible amount of possibility and potential for us, and particularly for us as creatives, as designers, as people who are making things in the world. This is the greatest creative challenge of our lives. There is a frog global effort to formalize a lot of the amazing work that we’ve already been doing in the space and to systematize some of the knowledge that we’ve been gathering by doing this work. So stay tuned for more, because I think in the next few months we’re definitely going to be launching some of those offerings more formally.

We want to sincerely thank Sesh for sharing her research and her time. Subscribe to the Design Mind frogcast wherever you listen to podcasts, including Apple Podcasts and Spotify. And if you have any thoughts about the show, we’d love to hear from you. Reach out at frog.co/contact.

Sesh is Strategy Director in frog’s London studio. She has over a decade of experience in strategy, service design, user research and management consulting. Sesh believes in the power of design and innovation as a force to build a world that works regeneratively and equitably for all. She uses a trans-disciplinary approach to help clients identify whitespace opportunities and build products, services and experiences that meets user needs and creates value for everyone. Sesh champions DEI efforts at frog and has also established and led a non-profit org in London dedicated to closing the gender gap in innovation. [Website]

Elizabeth tells design stories for frog. She first joined the New York studio in 2011, working on multidisciplinary teams to design award-winning products and services. Today, Elizabeth works out of the London studio on the global frog marketing team, leading editorial content.

She has written and edited hundreds of articles about design and technology, and has given talks on the role of content in a weird, digital world. Her work has been published in The Content Strategist, UNDO-Ordinary magazine and the book Alone Together: Tales of Sisterhood and Solitude in Latin America (Bogotá International Press).

Previously, Elizabeth was Communications Manager for UN OCHA’s Centre for Humanitarian Data in The Hague. She is a graduate of the Master’s Programme for Creative Writing at Birkbeck College, University of London.

We respect your privacy

We use Cookies to improve your experience on our website. They help us to improve site performance, present you relevant advertising and enable you to share content in social media. You may accept all Cookies, or choose to manage them individually. You can change your settings at any time by clicking Cookie Settings available in the footer of every page. For more information related to the Cookies, please visit our Cookie Policy.

Our Studios